Quick take: If your hearing feels like someone turned down the treble and put a thin wall between you and voices, the issue might be mechanical—not just “age.” Otosclerosis is a common, often very treatable cause of hearing loss where one tiny bone stops moving the way it should. The good news: modern hearing aids and minimally invasive surgery offer excellent outcomes for many people.

First, a 30-second refresher: how hearing usually moves

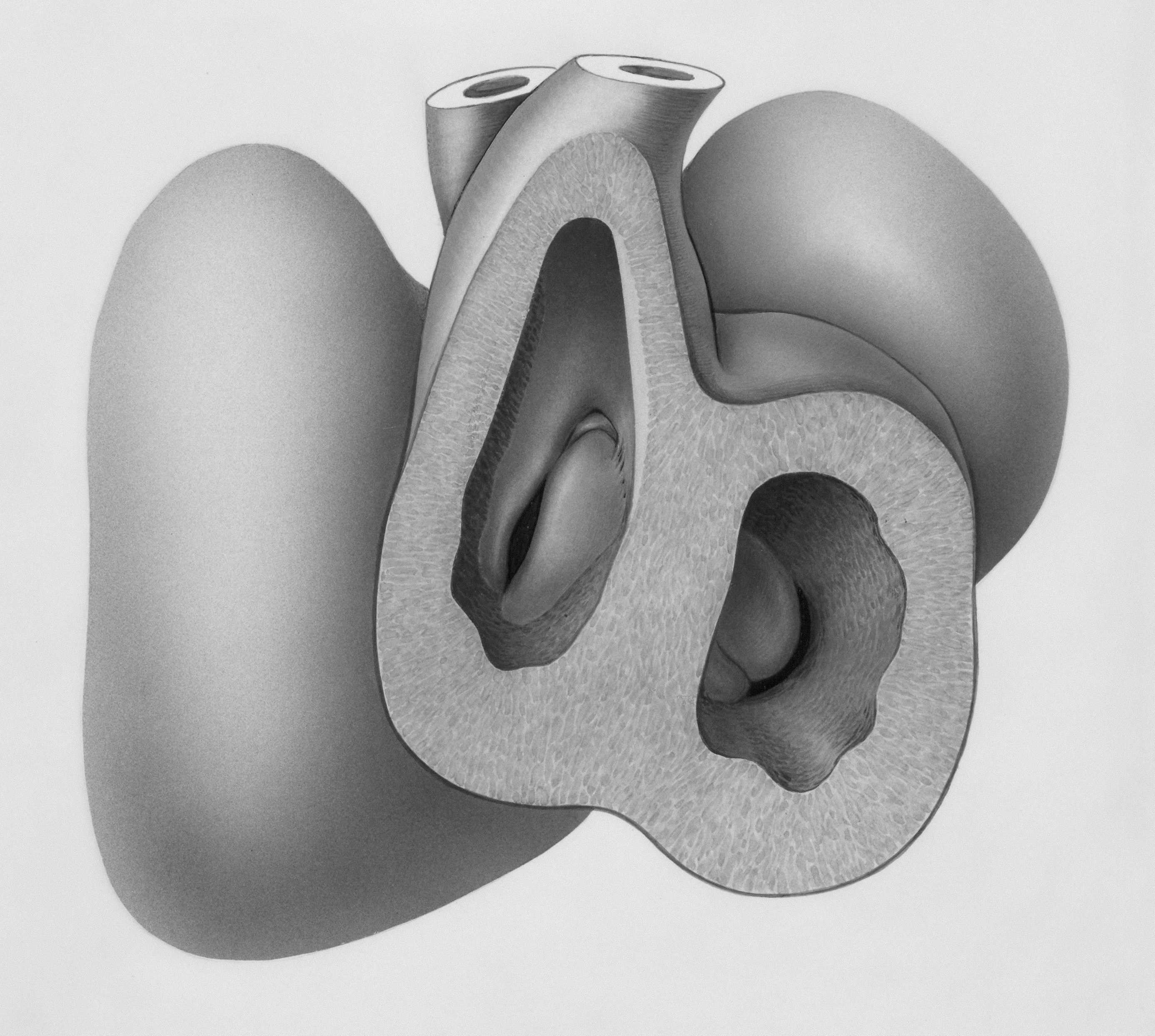

Sound is a relay race. The outer ear funnels waves to your eardrum. Three middle-ear bones—the malleus, incus, and stapes—pass that motion into the inner ear, where hair cells and the hearing nerve convert motion into electrical signals your brain understands as sound.

For clear hearing, those bones must move freely—especially the stapes, a tiny stirrup that presses on the inner ear’s “window.”

What is otosclerosis?

Otosclerosis is a bone remodeling condition of the middle and inner ear. New bone forms abnormally around the stapes footplate (and sometimes the cochlea), limiting its movement. When the stapes can’t rock easily, sound energy gets “stuck,” leading to hearing loss.

How it feels

- Voices are muffled, especially low-pitched male voices

- You hear better in quiet than in noisy places, but everyone sounds like they’re behind a door

- Tinnitus (ringing/buzzing) is common

- Family or friends notice you’re turning the TV up more

Some people with otosclerosis report a quirky phenomenon called paracusis of Willis: speech seems easier to hear in noisy environments because people talk louder—masking your loss.

Who tends to get it?

- Often begins in early-to-mid adulthood

- Can run in families

- Affects all genders; historically reported more often in women

- May affect one ear first, then both

Important note: Only a qualified clinician can tell if your hearing pattern fits otosclerosis or something else. Many conditions can mimic each other.

How clinicians figure it out

If otosclerosis is suspected, you’ll usually see an audiologist for tests and an ear specialist (otologist/ENT) to confirm and discuss options.

Common clues on a hearing test

- Conductive hearing loss: a gap between air and bone conduction thresholds on your audiogram

- Carhart notch: a dip around 2 kHz on bone conduction that can improve after surgery

- Normal eardrum mobility on tympanometry (because the eardrum is fine; the stapes is the issue)

- Absent acoustic reflexes (the reflex that tightens the middle ear muscles doesn’t trigger as expected)

Before surgery, some surgeons order a high-resolution CT scan of the temporal bone to map anatomy and rule out other causes.

If you're noticing the signs above, a hearing evaluation is the best next step. Early measurement doesn’t commit you to treatment—it gives you a baseline and choices.

Your options: from “watch and monitor” to “fix it”

1) Watchful waiting (with smart hearing habits)

If your hearing loss is mild and not bothersome, monitoring every 6–12 months is reasonable. Pair that with protective habits:

- Turn down recreational noise (concerts, lawn tools) and use quality hearing protection

- Keep heart and metabolic health in check; healthy vessels support a healthy inner ear

- Flag any new symptoms quickly (sudden changes, spinning vertigo, ear pain)

2) Hearing aids: amplify around the “stuck” bone

Modern hearing aids can beautifully overcome the mechanical bottleneck by delivering just-right amplification. Benefits:

- Clearer speech without blasting the room

- Custom prescription based on your audiogram, including bass boost if low tones are most affected

- Tinnitus relief features and soothing sound options

- Seamless life: phone streaming, TV connectors, directional microphones for noisy restaurants

Many people with otosclerosis do exceptionally well with hearing aids alone, especially if they prefer a non-surgical path or have mixed hearing loss (both conductive and sensorineural components).

3) Stapes surgery: tiny move, big payoff

If the stapes is fixed, an ear surgeon can create a small opening in the stapes footplate and place a piston-like prosthesis that restores motion to the inner ear. This is called a stapedotomy (or less commonly, a stapedectomy, where more of the footplate is removed).

What to expect:

- Usually an outpatient procedure through the ear canal

- Hearing often improves within days to weeks, with continued fine-tuning as healing occurs

- Success rates are high for closing the “air-bone gap” in the right candidates

Risks to discuss (overall uncommon, but important):

- Temporary dizziness or imbalance during healing

- Changed taste on one side of the tongue (chorda tympani nerve irritation)

- Tinnitus changes (can improve, stay the same, or rarely worsen)

- Sensorineural hearing loss or “dead ear” is rare but serious—discuss your individual risk with your surgeon

Even after a successful surgery, some people still choose (or later add) a hearing aid for the best clarity, especially if there is a sensorineural component.

4) Advanced options

- Bone conduction devices can bypass the middle ear for certain patterns of loss

- Cochlear implants may be considered in severe, advanced otosclerosis affecting the cochlea

A specialty ear center can help you weigh these choices based on your audiogram and goals.

Living well with otosclerosis

Conversation upgrades that help today

- Face the person speaking; lip and facial cues add “bonus subtitles” for your brain

- Choose seating with your better ear toward the speaker and your back to noise

- Use real-time captions for calls and meetings when possible

- Pair your hearing aids to your phone for direct streaming and clearer calls

Tinnitus: turn down the brain’s alarm

- Amplification often reduces tinnitus by restoring sound input

- Use neutral sound (soft rain, fan, ocean) at low levels to make ringing less intrusive

- Stress reduction helps; the brain’s “volume” knob for tinnitus and stress is shared

If tinnitus spikes, or if it’s new and one-sided, loop in an audiologist or ENT for a check-in.

Myths, busted

- “There’s nothing to do.” False. Many people get excellent benefit from hearing aids, and stapes surgery can dramatically improve hearing in the right candidates.

- “It only affects older adults.” False. It often starts in early-to-mid adulthood.

- “Surgery is a one-and-done cure.” Not always. Hearing can change over time, and some people still use hearing aids for best clarity.

What about hormones and pregnancy?

Historically, some reports suggest otosclerosis symptoms may progress during pregnancy or hormonal shifts. Not everyone experiences this, and research is mixed. The practical takeaway: if you have (or suspect) otosclerosis and are planning pregnancy, let your audiologist and ENT know. Baseline testing and follow-up make it easier to spot and manage changes early.

Questions to bring to your appointment

- Does my audiogram look more like conductive, sensorineural, or mixed loss?

- Based on my results, would you recommend trying hearing aids first, considering surgery, or both?

- What outcomes and risks apply to me if we consider stapedotomy?

- How often should we monitor my hearing if I’m not ready for treatment?

- Could anything else be causing a similar pattern (e.g., eardrum problems, ossicular chain issues)?

The bottom line

Otosclerosis is a mechanical issue with a modern toolkit of solutions. If voices feel muffled and you’re riding the volume button, don’t tough it out. A comprehensive hearing evaluation can confirm what’s happening and open the door to clearer, more effortless listening—whether that’s with expertly fit hearing aids, a precise outpatient surgery, or both.

Ready for clearer hearing? Book a hearing test with a licensed audiologist, and ask whether an ENT consultation makes sense for you.

Further Reading

- The Stuck Stapes: Otosclerosis and the Fixable Hearing Loss (Hearing Loss) - When One Ear Falls Behind: Why Asymmetric Hearing Loss Matters (and What to Do) (Hearing Loss) - Sudden Hearing Loss, Fast Action: Your First 48 Hours (Hearing Loss) - Sudden Hearing Loss: The 72-Hour Treatment Playbook (What to Do Now) (Treatment)Frequently Asked Questions

Is otosclerosis dangerous?

It isn’t life-threatening. The main issue is progressive hearing loss that can strain communication and quality of life. The encouraging part: hearing aids and stapes surgery both offer effective ways to restore usable hearing for many people. If you suspect otosclerosis, an audiologist and ENT can guide safe, personalized options.

Will surgery restore my hearing to normal?

Many people experience a big improvement in clarity and volume, especially for the conductive part of the loss. Outcomes vary with your starting hearing, ear anatomy, and any sensorineural component. Some people still benefit from a hearing aid after surgery for fine-tuned clarity. Your surgeon can share likely ranges based on your audiogram.

What’s the difference between stapedotomy and stapedectomy?

Both aim to bypass the fixed stapes. A stapedotomy creates a tiny hole in the stapes footplate and places a piston prosthesis. A stapedectomy removes more of the footplate before placing a prosthesis. Today, stapedotomy is more common because it preserves more natural structures while reliably restoring movement.

Can otosclerosis cause tinnitus or dizziness?

Yes. Tinnitus is common and often improves with better hearing—through amplification or surgery. Brief dizziness can occur right after surgery as the ear heals. Persistent or severe vertigo is uncommon; if you have it, let your clinician know promptly.