If you’ve been told you have otosclerosis, you’re not alone—and you do have options. The good news is that most people do very well with treatment, whether that means wearing modern hearing aids or choosing a minimally invasive ear surgery called a stapedotomy. This guide walks you through the trade‑offs so you can make a confident, personalized decision with your audiologist and ear surgeon.

What is otosclerosis, in plain language?

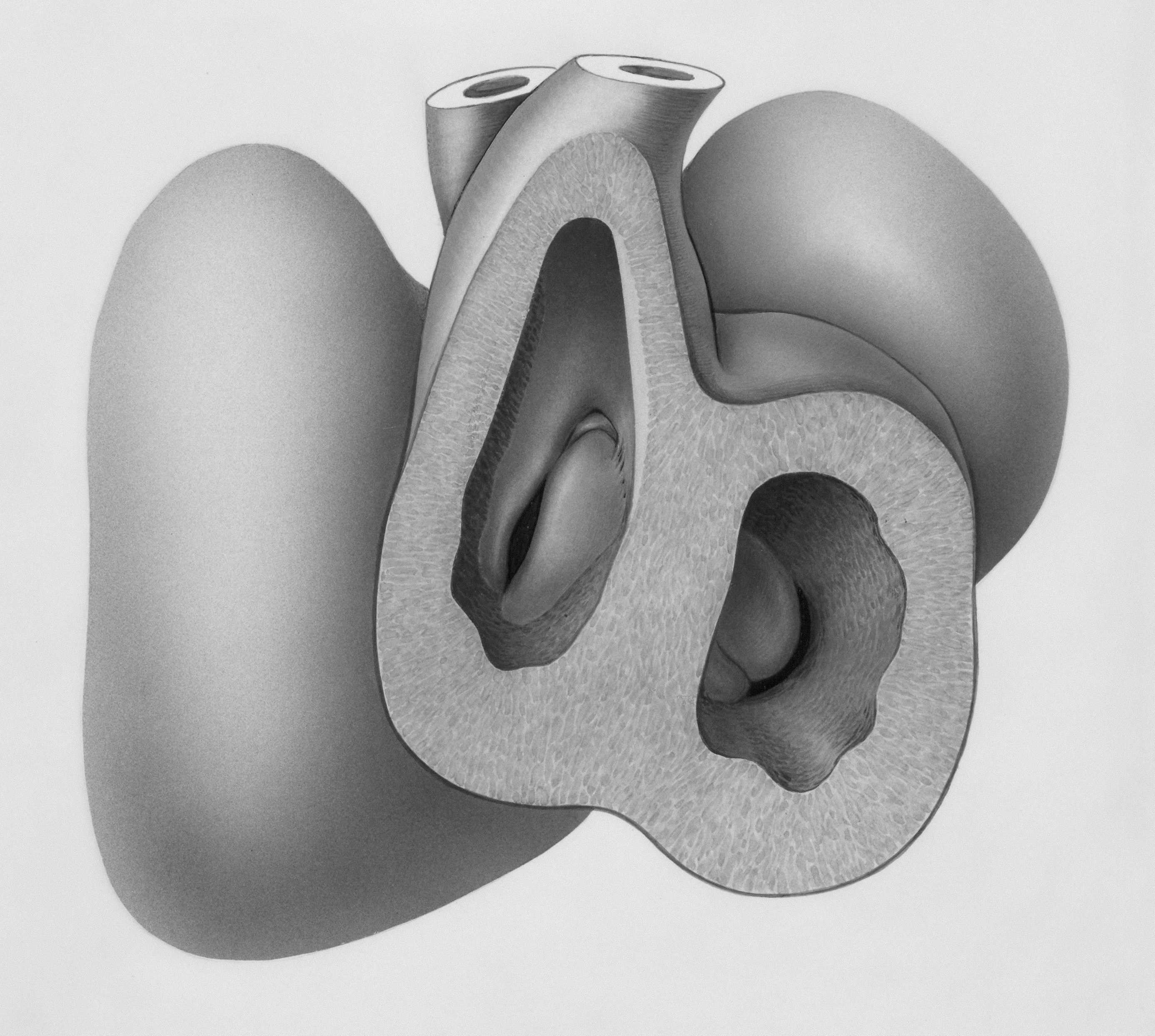

Otosclerosis is a condition where new bone forms abnormally around the stapes—the stirrup-shaped bone in the middle ear. That extra bone reduces the stapes’ movement, making sound transmission less efficient. The result is typically a conductive hearing loss (sound is blocked or dampened in the middle ear). Some people also have a sensorineural component (inner-ear involvement), especially as the condition progresses.

Common experiences people report include:

- Gradually worsening hearing (often in one ear first, then both)

- More trouble hearing low-pitched voices or in groups

- Ringing or buzzing (tinnitus)

- Family history of similar hearing patterns

Diagnosis is made by an audiologist and ENT/otologist using a hearing test (audiogram and tympanometry), medical exam, and sometimes imaging. If you haven’t had a full workup, make that your first step.

Your two primary treatment paths

For most adults with otosclerosis, treatment falls into two well-established categories:

- Hearing aids that amplify sound to overcome the middle‑ear blockage

- Stapedotomy (or stapedectomy), a microsurgery that replaces the fixed stapes with a tiny prosthesis so sound moves normally again

Both can deliver excellent everyday hearing. The right choice depends on your hearing profile, health, lifestyle, comfort with surgery, and personal preferences.

Option 1: Hearing aids for otosclerosis

How they help

Modern hearing aids can effectively “bridge” the stiffness of the stapes by amplifying sound precisely in the frequencies where you need it. For many, they restore conversational ease, keep you engaged socially, and reduce listening effort.

Who often does best with hearing aids

- Mild to moderate conductive hearing loss

- Medical factors that make surgery less appealing

- Desire to avoid the risks (even small ones) of surgery

- Preference for a reversible, adjustable solution

Pros

- Immediate benefit once fitted and tuned

- Non-invasive and reversible

- Customizable for changing hearing over time

- Tinnitus support via masking/sound therapy features

Cons

- Ongoing maintenance (cleaning, periodic fittings)

- Battery changes or recharging

- Out-of-pocket cost varies; insurance coverage differs

- Doesn’t “fix” the underlying stapes fixation

Real-world tips for success

- Prioritize fit and real-ear verification. Ask your audiologist to measure sound in your ear canal and tune amplification to your exact hearing profile.

- Stability matters. Because otosclerosis can progress, schedule regular hearing checks so your settings can keep pace.

- Lean into features. Directional microphones, Bluetooth streaming, and dedicated programs for restaurants can boost performance in noise.

- Consider style and comfort. Both behind-the-ear and in-the-ear styles can work well for conductive loss; let sound quality and comfort lead the decision.

Option 2: Stapedotomy (and stapedectomy)

What the surgery does

In otosclerosis, the stapes becomes fixed. In a stapedotomy, an ear surgeon (otologist) makes a very small opening in the footplate of the stapes and places a tiny prosthesis that connects the eardrum’s bones to the inner ear again. A stapedectomy removes more of the footplate; today, stapedotomy with a microdrill or laser is more common.

Expected results

- High success rates. Many studies report closure of most of the air‑bone gap and meaningful improvement in speech hearing in the operated ear.

- Tinnitus often improves when hearing improves, though results vary.

- One‑time procedure for many; some need later adjustments or revision, but most do not.

Risks to discuss with your surgeon

- Inner‑ear hearing change. A small risk of permanent sensorineural hearing loss in the operated ear exists.

- Dizziness. Temporary imbalance or vertigo is common for a few days; prolonged issues are less common.

- Taste changes. The chorda tympani nerve runs through the middle ear; temporary metallic taste or tongue numbness can occur, occasionally longer‑lasting.

- Ear canal or eardrum issues. Infection, tearing, or scarring are uncommon but possible.

- Prosthesis problems. Rare displacement or need for revision.

Anesthesia and recovery

- Outpatient surgery under local anesthesia with sedation or general anesthesia, depending on surgeon and patient.

- Activity limits for 1–2 weeks: avoid heavy lifting, nose-blowing, and pressure changes as directed.

- Hearing timeline: Many notice improvement quickly, but fullness or fluctuating hearing is common in the first few weeks. Your surgeon will guide when to test hearing post‑op.

Who often does best with surgery

- Clear otosclerosis with a significant air‑bone gap on testing

- Good overall health and middle-ear status (no active infection)

- Strong desire for a one‑time procedure that restores natural sound transmission

- Comfort with the small but real risks of ear surgery

How to choose: A practical decision framework

There isn’t a universally “right” choice; there’s a “right for you” choice. Consider these lenses:

1) Your audiogram and exam

- Predominantly conductive loss with a healthy inner ear tends to respond especially well to stapedotomy.

- Mixed loss (conductive + sensorineural) can still benefit from surgery, but the inner-ear component will remain. Some people still prefer hearing aids first—or combine approaches.

2) Your lifestyle and goals

- I want low maintenance and natural sound: surgery may appeal.

- I prefer adjustability and zero surgical risk: hearing aids may fit better.

- I need top performance in noise and streaming: hearing aids offer tech features you might value daily.

3) Your timeline and tolerance for recovery

- Fast, predictable improvement without downtime favors hearing aids.

- Willing to take a short recovery for a potential long‑term fix favors surgery.

4) Cost and coverage

- Hearing aids: Out‑of‑pocket costs vary widely by brand and service plan; some insurance plans or employer benefits contribute. Aids typically last 4–6 years.

- Surgery: Often covered when medically indicated. You may still have deductibles or co‑insurance. Ask the clinic’s billing team for a realistic estimate.

5) Emotional comfort

Some people feel uneasy about any ear surgery; others value a one‑time fix. There’s no wrong feeling—choose the path that aligns with your comfort and support system.

Can you combine approaches?

Absolutely. Common scenarios include:

- Surgery in one ear, hearing aid in the other. Helpful when both ears are involved at different levels.

- Hearing aid first, surgery later. Many use hearing aids for years and opt for surgery when life or hearing needs change.

- Surgery first, hearing aid later. If inner-ear hearing declines with age (as it does for most of us), a future hearing aid can fine‑tune clarity while the middle‑ear mechanics remain restored.

What about bone‑anchored systems?

If traditional hearing aids haven’t worked well for you, and surgery isn’t a fit or hasn’t provided sufficient benefit, bone‑anchored hearing devices (BAHD/BAHA) can route sound via bone conduction to the inner ear, bypassing the middle ear. These can be worn on a softband or attached via a small implant placed by an ENT surgeon. Ask your audiologist if you’re a candidate.

Special considerations to discuss with your care team

- Tinnitus: Both hearing aids and successful stapedotomy can reduce tinnitus by improving auditory input. If tinnitus is a major concern, discuss expectations and additional tinnitus therapies with your audiologist.

- Dizziness history: If you’re prone to vertigo, your surgeon will tailor counseling and precautions.

- Taste changes: Temporary metallic taste is not unusual after surgery; it typically fades. Ask how often your surgeon sees long‑term changes.

- Future hearing changes: Otosclerosis can progress, and age‑related hearing changes are common. Plan for ongoing checks and flexible strategies.

Your next steps

- Get a complete diagnostic workup. If you haven’t already, schedule a comprehensive hearing test and ENT/otology evaluation. Clarify whether your hearing loss is predominantly conductive, mixed, or sensorineural.

- Request side‑by‑side counseling. Ask your audiologist and surgeon to walk you through expected outcomes for you specifically—based on your audiogram, middle‑ear status, and medical history.

- Trial the technology. Many clinics offer hearing aid trials. Experiencing real‑world listening can help you compare to expected surgical outcomes.

- Get a transparent cost picture. Ask about device costs, service plans, and surgical coverage so finances don’t cloud the decision later.

If you’re feeling stuck, a second opinion from a fellowship‑trained otologist can be invaluable. Your hearing is central to how you connect with the world—you deserve clarity and confidence in the path you choose.

Quick answers to common “what ifs”

How long does a stapes prosthesis last?

Many last for decades. While any implant can rarely need revision, most people enjoy long‑term stability after a successful procedure.

Will surgery fix hearing in noise?

Surgery restores the middle‑ear mechanics; it doesn’t add directional microphones or noise reduction. Many patients hear more naturally after surgery, but you may still want communication strategies or assistive mics in difficult environments—just as anyone does in loud spaces.

If I choose hearing aids now, am I closing the door on surgery later?

No. Using hearing aids does not preclude a future stapedotomy. In fact, staying engaged and hearing well now can support your brain’s ability to process sound over time.

A realistic expectation snapshot

- With hearing aids: Expect clearer conversation, better participation, and adjustable support as your hearing evolves. Plan on periodic cleanings, tune‑ups, and battery/charging routines.

- With stapedotomy: Expect a short recovery, a noticeable improvement in the operated ear’s loudness and clarity, and a small but meaningful risk profile to consider. Plan on follow‑up visits and hearing checks.

Both roads can lead to confident, connected hearing. The best one is the one that fits you.

Gentle reminder: This article is educational and can’t replace personalized medical guidance. Partner with a licensed audiologist and an ENT/otologist to map your next steps.

Frequently Asked Questions

Will otosclerosis go away on its own?

Otosclerosis doesn’t typically reverse on its own. Some people notice periods where changes seem to slow. Because hearing can progress over time, regular audiology follow‑ups help you adjust treatment early and stay connected.

Is fluoride or medication a proven treatment for otosclerosis?

Medications like sodium fluoride or bisphosphonates have been studied, but high‑quality evidence for routine use is limited and practice varies. Discuss potential benefits and risks with your ENT specialist; surgery and hearing aids remain the most established treatments.

How soon can I fly or work out after stapedotomy?

Your surgeon will give specific timelines. In general, people avoid heavy lifting, straining, and pressure changes for about 1–2 weeks. Many can fly after their first post‑op check when the ear has started to heal, but always follow your surgeon’s guidance.

Does surgery help tinnitus from otosclerosis?

For many, tinnitus improves as hearing improves after a successful stapedotomy. It’s not guaranteed, and some people continue to notice tinnitus. Hearing aids, sound therapy, and counseling can also help manage tinnitus day to day.

References

- Mayo Clinic – Otosclerosis

- NIDCD (NIH) – Otosclerosis

- StatPearls – Otosclerosis (updated 2024)

- American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery – Otosclerosis Patient Information