What if a small blood sample could tell you your ears took a hit at last night’s concert—before your hearing test changes? That’s the moonshot behind new “ear biomarkers,” a fast-moving research frontier that aims to flag inner-ear stress earlier and more precisely than today’s tools. Here’s what scientists are finding, why it matters, and how to protect your hearing right now while the lab work catches up.

First, why biomarkers could be a game-changer

Biomarkers are measurable signals from the body—proteins, tiny RNAs, electrical responses—that reveal what’s happening inside. In cardiology, we use troponin to detect heart muscle injury. In hearing, we’ve long relied on behavioral tests (raise your hand when you hear the beep) and functional tests (otoacoustic emissions, speech-in-noise) to infer cochlear health. They’re essential, but they don’t directly tell us what cells are stressed or when injury started.

Enter biomarkers. If we can reliably measure molecules that leak or change when inner-ear structures are stressed, clinicians could:

- Detect damage earlier—possibly before a standard audiogram shows loss

- Monitor risk in people exposed to noise or ototoxic drugs

- Tailor protection and recovery plans to the type of injury

- Shorten the guesswork when symptoms are confusing (ringing, fullness, dizziness)

We’re not fully there yet. But the lab bench is getting closer to the clinic—fast.

What’s being measured now (and why it’s exciting)

1) Prestin: a protein from your outer hair cells

Prestin is the tiny “motor” protein that lets outer hair cells amplify soft sounds. In animal models and early human studies, blood levels of prestin change after loud sound exposure and certain inner-ear injuries. Think of prestin as a smoke alarm for outer hair cell stress.

Where we are:

- Research suggests prestin in blood may rise or fall depending on timing after noise exposure.

- It’s not yet standardized for clinical use—assays, timing, and normal ranges are still being refined.

Why it matters: If validated, a prestin blood test could one day help identify noise damage before you notice trouble understanding speech in noise.

2) Cochlin-tomoprotein (CTP): a potential clue for perilymph leaks

Cochlin is abundant in the inner ear. A fragment called cochlin-tomoprotein (CTP) has been used in some centers (not widely in the U.S.) to help detect perilymphatic fistula—an abnormal leak of inner-ear fluid that can follow trauma or barotrauma and cause hearing changes, dizziness, or pressure sensations.

Where we are:

- CTP testing of middle-ear fluid has been explored, particularly in Japan, to support diagnosis of suspected leaks.

- It’s not a routine test everywhere; access and protocols vary by region and specialist.

Why it matters: A reliable marker of a perilymph leak could speed targeted care. If you’ve had sudden ear fullness after strain, pressure changes, or head injury, talk with an ENT or neurotologist promptly.

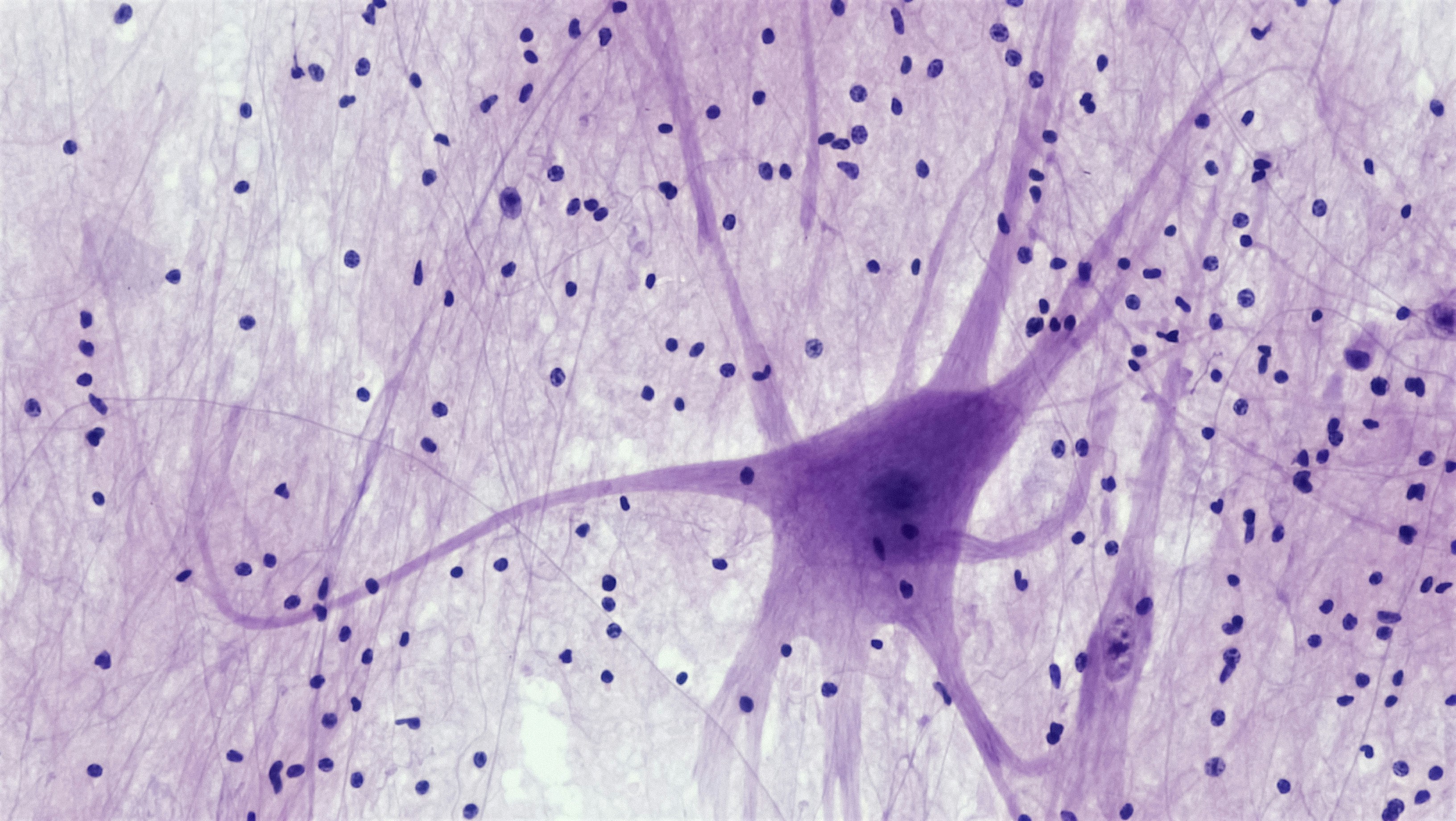

3) MicroRNAs: whisper-level messengers of cellular stress

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are tiny regulators that turn genes on and off. Several miRNAs shift after noise exposure and ototoxic drugs in animal studies, and early human data are emerging.

Where we are:

- They’re promising as early “fingerprints” of inner-ear stress, but tests are not clinic-ready.

- Researchers are mapping which miRNAs track specific injury types (e.g., synapse vs. hair cell).

Why it matters: A panel of miRNAs could someday tell clinicians what part of the auditory pathway is hurting—and when.

4) Inflammation and oxidative stress markers

Noise and certain medications can spark inflammation and oxidative stress in the cochlea. Blood markers like cytokines or oxidative stress byproducts are being studied as indirect indicators of ear injury.

Why it matters: These are nonspecific—they rise in many conditions—but combined with ear-specific signals, they could sharpen the picture.

5) Ototoxicity monitoring: protecting ears during life-saving treatments

Chemotherapy agents (like cisplatin) and some antibiotics can damage inner-ear cells. Researchers are testing biomarker “signatures” that might predict who’s most vulnerable or flag early injury so treatment can be adjusted.

Why it matters: Objective, early warning could help oncologists and audiologists coordinate protective strategies when possible. If you’re starting a known ototoxic medication, ask your care team about baseline and ongoing hearing monitoring.

Not just blood: functional and physiologic biomarkers you may hear about

Otoacoustic emissions (OAEs)

OAEs are tiny echoes your cochlea generates; they’re a sensitive, noninvasive window into outer hair cell health. DPOAEs can drop after loud sound exposure even when a standard audiogram looks normal.

Takeaway: If you work in noise or attend frequent loud events, getting OAEs measured alongside an audiogram gives a more complete baseline.

Pupillometry for listening effort

Your pupils quietly dilate when listening is hard. Scientists use this to quantify listening effort—how much “brain fuel” you’re spending to understand speech in noise. It won’t diagnose hearing loss, but it helps evaluate how well hearing aids and features reduce effort.

Electrophysiology: EFRs and ABRs

Envelope following responses (EFRs) and auditory brainstem responses (ABRs) measure how well the auditory system tracks sound. Researchers use them to probe “hidden” neural changes (e.g., synapse stress) that don’t always show up on a basic audiogram. These tests remain primarily research tools, but some clinics use ABRs in specific cases.

What this means for you today

Let’s be real: You can’t walk into a clinic today and order a “concert damage” blood test. But you can act on what we already know and set yourself up to benefit from the next wave of tools.

- Get a baseline: Establish an audiogram and OAEs if possible—especially if you work in noise, love live music, or are starting an ototoxic medication.

- Monitor your sound dose: Use a smartphone or smartwatch’s exposure features and keep daily averages under safe limits. Follow the 60/60 rule for earbuds (≤60% volume for ≤60 minutes, then rest).

- Protect consistently: Carry high-fidelity earplugs; choose over-ear hearing protection for power tools, yard work, or concerts.

- Ask about monitoring if on ototoxic meds: Coordinate with your oncologist or prescribing clinician and an audiologist for regular checks.

- Don’t ignore symptoms: New tinnitus, fullness, muffled hearing, sudden dizziness after strain or pressure changes—get prompt care from an audiologist or ENT. Early evaluation matters.

If you’re unsure where to start, a quick consult with an audiologist can personalize a plan and translate research into practical steps for your life.

What to watch next

- Standardized prestin assays: Clear timing windows and reference ranges would move this protein toward clinical utility.

- Biomarker panels: Combinations of miRNAs, proteins, and functional tests may outperform any single marker.

- Clinical validation: Larger human studies across ages, noise exposures, and medications will determine real-world usefulness.

- Point-of-care testing: The dream is a small, fast test that supports quick decisions after exposure or during treatment.

Progress isn’t linear, but it’s steady. Expect incremental wins—better risk stratification for noisy jobs, smarter hearing conservation programs, and earlier flags for vulnerable patients—long before a universal “ear damage strip test” lands in pharmacies.

Lower your ear’s “biomarker risk” daily

While we wait for lab tests to mature, your daily habits are powerful medicine for your ears.

- Control volume and time: Sound level plus duration drives risk. Keep personal audio under 60% and take listening breaks.

- Level up protection: At concerts, wear musicians’ earplugs; for lawn equipment or DIY projects, use earmuffs with a high NRR.

- Mind your cardio-metabolic health: Healthy blood pressure, glucose, and activity support the inner ear’s demanding energy needs.

- Sleep and recharge: Rest supports recovery from temporary threshold shifts after loud sound.

- Plan ahead for big sound days: Pack earplugs, charge hearing protection with active noise reduction if you use it, and set volume limits on devices.

And remember: technology enhances, but doesn’t replace, expert care. If you’re navigating tricky symptoms or high-risk exposures, loop in an audiologist or ENT for tailored guidance.

Bottom line

Ear biomarkers are moving from sci‑fi to “soon-ish.” We can’t yet prick a finger and see exactly what last night’s decibels did, but the pieces are coming together—prestin, miRNAs, OAEs, and more. In the meantime, the best strategy is simple and strong: know your baseline, manage your sound dose, and partner with hearing pros who can interpret both today’s tests and tomorrow’s breakthroughs.

Further Reading

- Pregnancy and Your Hearing: The Surprising Ear Changes (and How to Handle Them) (Hearing Loss) - Can We Regrow Hearing? The Real State of Hair Cell Regeneration (Research) - Your Heart, Your Hearing: The Cardiometabolic Link You Can’t Afford to Ignore (Research) - Hidden Hearing Loss Is Real: Why a Normal Audiogram Can Still Leave You Struggling in Noise (Research)Frequently Asked Questions

When will a simple blood test tell me if a concert hurt my hearing?

Not yet. Prestin and other candidates are promising, but they need standardized tests, timing guidelines, and large human studies. Realistically, think in terms of years, not months. Right now, the best early indicators after loud sound are symptoms (ringing, fullness) and changes in otoacoustic emissions. If you’re concerned after an exposure, book an audiology check.

Is the cochlin-tomoprotein (CTP) test available in the United States?

CTP testing has been reported more often in Japan and select centers; it’s not widely available in the U.S. If an ENT suspects a perilymphatic fistula, diagnosis is usually based on history, exam, and a combination of tests and imaging. Ask your ENT or neurotologist about current options in your region.

Can my smartwatch tell me if my inner ear is damaged?

Smartwatches can estimate your sound exposure and nudge you when levels are risky—a great prevention tool. They can’t detect inner-ear cell damage. Pair your device’s exposure alerts with regular hearing checks, especially if you’re often in loud environments.

I’m starting chemotherapy. Can biomarkers protect my hearing?

Biomarker research is underway, but the practical step today is a monitoring plan: baseline audiogram and OAEs before treatment, then scheduled rechecks. Bring up hearing with your oncology team and ask for an audiology referral. Early changes sometimes allow adjustments to lower risk when medically appropriate.